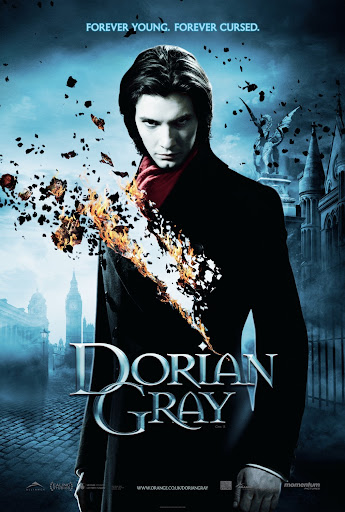

Dorian Gray

2009

Rated R

1 hr. 52 mins.

Momentum Pictures/Ealing Studios

Directed by Oliver Parker

Starring Ben Barnes, Colin Firth, Ben Chaplin, Rebecca Hall

A corrupt young man somehow keeps his youthful beauty eternally, but a special painting gradually reveals his inner ugliness to all. [IMDb)

When Oscar Wilde wrote his one-and-only novel (“The Picture of Dorian Gray,” published as a novella in “Lippincott's Monthly Magazine,” 1890; and in longer form one year later), it’s fair to say he had no idea that it would remain so permanently threaded in the fabric of society. Wilde’s novel is a shrewd commentary on culture’s perception of–-and obsession with–-youth and beauty, which is all the more poignant today's society than it was in the late-Victorian era. To this day, if someone seems to be defying the inevitable aging process, we pause to wonder: “Do they have a painting in their attic?”

There have been scads of film, TV, and stage adaptations of what is considered Wilde’s most popular work–-barring his extremely clever and witty stage plays, namely “The Importance of Being Earnest”, “An Ideal Husband”, and “Lady Windermere’s Fan’. Arguably, the most well-known feature-length film version is Oliver Parker’s 2009 “Dorian Gray”, which stars Ben Barnes in the title role, Colin Firth as the dastardly Lord Henry Wotton, and Ben Chaplin as the ill-fated portrait painter Basil Hallward. Before we delve into the various themes Wilde focused on in the novel and how those play out on the big screen, I’ll provide a plot synopsis. Naturally, the film does differ from the book in several major ways, but essentially all the moving pieces are present and accounted for:

Dorian Gray, a naive and sheltered young man, inherits the estate of his deceased grandfather turning him into a proper English gentleman overnight. He is immediately befriended by the upper echelon of Victorian London, developing a fast friendship with the much-ballyhooed portrait painter Basil Hallward. Through Hallward, he is introduced to Lord Henry Wooton, who becomes the architect of Dorian’s downfall.

Although Dorian is keenly aware he possesses staggeringly good looks, his personality initially lacks conceit and his morals are safely intact. Everything changes as soon as the cynical and acid-tongued Lord Henry opens his mouth to spew his nihilistic philosophies on life. Events are triggered when Hallward’s finished portrait of Dorian is revealed. Lord Henry posits that unlike Dorian, the painting will never age. He asks Dorian if he’d be willing to bargain his soul in exchange for everlasting youth. Dorian admits he would. And, as if by some mischief or magic (neither Wilde or the 2009 film explain precisely how), Dorian’s soul and the painting become enmeshed. From that moment on, he stops aging and soon begins to notice that the portrait is aging in his place.

|

| Ben Barnes in the role of Dorian Gray (2009) |

Throughout the book and film, Dorian is extremely suggestible and easily led by Lord Henry’s silver-tongued philosophies. He warps the young innocent's mind for sport. In no time, Dorian takes on Lord Henry's penchant for partaking in society’s hedonistic pleasures–including opiates, heavy drinking, and prostitution. Early on, Lord Henry thwarts Dorian’s engagement to a naive young actress, who commits suicide when the marriage is called off–-an event that will haunt him for the remainder of his life. From here on, Dorian’s personal character shifts dramatically.

|

| Firth and Barnes in Dorian Gray (2009) |

Under Lord Henry’s influence, Dorian slips into the rabbit hole of seedy London nightlife. With each misdeed and exploited vice, his portrait ages further–-taking on hideous characteristics that visually represent his evildoings. Both horrified by his strange new reality and desperate to make sure his bargain is kept, he hides the portrait in an attic chamber. In his most desperate act, he murders Hallward when the unwitting painter discovers the truth about Dorian’s ageless beauty.Decades pass, and Dorian has become a pro at leading a double life; but that doesn’t mean his reputation hasn’t suffered nor stopped people from gossiping about his ever-youthful appearance. From here, in what is the most obvious deviation from the source material, Dorian seeks redemption by falling in love with the principled daughter of Lord Henry. So distraught by their impending union, Lord Henry seeks to uncover Dorian’s secret, finds the painting, and confronts Dorian, who chooses to sacrifice himself in order to save his friend and the woman he had hoped could save him from himself.

“Behind every exquisite thing that existed, there was something tragic.”

Let’s take a few moments to consider this theme, along with others presented in both the film and the book and apply them to the climate of late-Victorian society. Wilde lived during what was perhaps the most hypocritical era of Western history. On the surface, Victorians were moral and upright; extremely guarded in all personal matters; critical of others who dabbled in anything labeled taboo; and bound by strict and convoluted rules of social etiquette. The irony being, more often than not, these same Victorians were addicted to legal and illegal substances; frequenting houses of ill-repute; having extra-marital affairs or keeping mistresses among other less-than-moral behaviors. (One glaring for instance: Let’s not forget how quickly the invention of modern pornography followed the invention of the camera.) “The Picture of Dorian Gray” was, and remains, a statement on how if one scratched below the surface, they’d find a very different Victorian society underneath. Beauty is, after all, only skin deep.

|

| Chaplin and Barnes in Dorian Gray (2009) |

Why the anticipatory censorship? We must remember the time in which the book was written, and that Wilde was living a double life himself. Married, but engaging in relationships with men--not unlike many men in the Victorian era who did the same and kept each other's secrets. Wilde chose to reveal through clever subtext and passing anecdotes that Dorian, Lord Henry, and Hallward were all engaged in same-sex liaisons–and, more than likely, with each other. (For example, the novel contains a subtle reference to Dorian and Lord Henry sharing a house while vacationing in Tangiers--a destination known to be frequented by gay men during the Victorian era--with purposeful intent.)

While Wilde was restricted from using this theme overtly because homosexuality was illegal and subject to criminal conviction, the film does a thorough job expressing it. Under Lord Henry’s influence, Dorian engages in many types of sexual encounters. In today’s vernacular, he would most likely be considered pansexual. How these encounters are represented on film, however, does warrant some criticism. It’s not that the various acts that take place in the film didn’t exist at the time; they certainly did. Hell, the Victorians probably invented some of them. But, I do question the emphasis and screen time given to these encounters. At times, it does seem gratuitously presented for the sake of shock value and eroticism rather than for the purposes of moving the plot along or defining character. That being said, while those scenes are shocking, they are sexy and erotic, as well as artistically filmed and edited.

|

| Barnes en flagrante delecto in Dorian Gray (2009) I'd show you others, but they're simply NSFW. This was the tamest of the lot. |

|

| Barnes as Dorian Gray confronts his demons. |

|

| (Scroll for more style comparisons.) |

With respect to art direction, this film is a veritable feast for the eyes. From set dressing to costuming, everything feels authentically–and sumptuously–Victorian. The wardrobe team was definitely doing their due diligence when it came to dressing Dorian. I’ve no doubt they modeled the look on the author himself, using portraits taken of Wilde, namely those by photographer and lithographer Napoleon Sarony, for inspiration. (In addition to the image shown to the left, I’ve put together a small collection of examples to prove my hunch. Scroll to the end of the posting for a look.)

Overall, "Dorian Gray" is an entertaining, if unreliable adaptation of Wilde’s work. Watch it for entertainment value, but not for the basis of writing your book report. ;)